Randolph Series: The End

by Anna Cooper—Associate Editor

Photography by Scott Taylor

When we started talking about Randolph in our Memories Series we didn’t foresee the current events that were coming our way. This series of articles were written to clearly and concisely define the once-bustling city’s history and all that it entails. Just like the Roman Empire, it came and it went, but Randolph doesn’t deserve to be lost to the annals of time. This portion of Randolph’s history explores its part in the Civil War and the consequences of its role in the war.

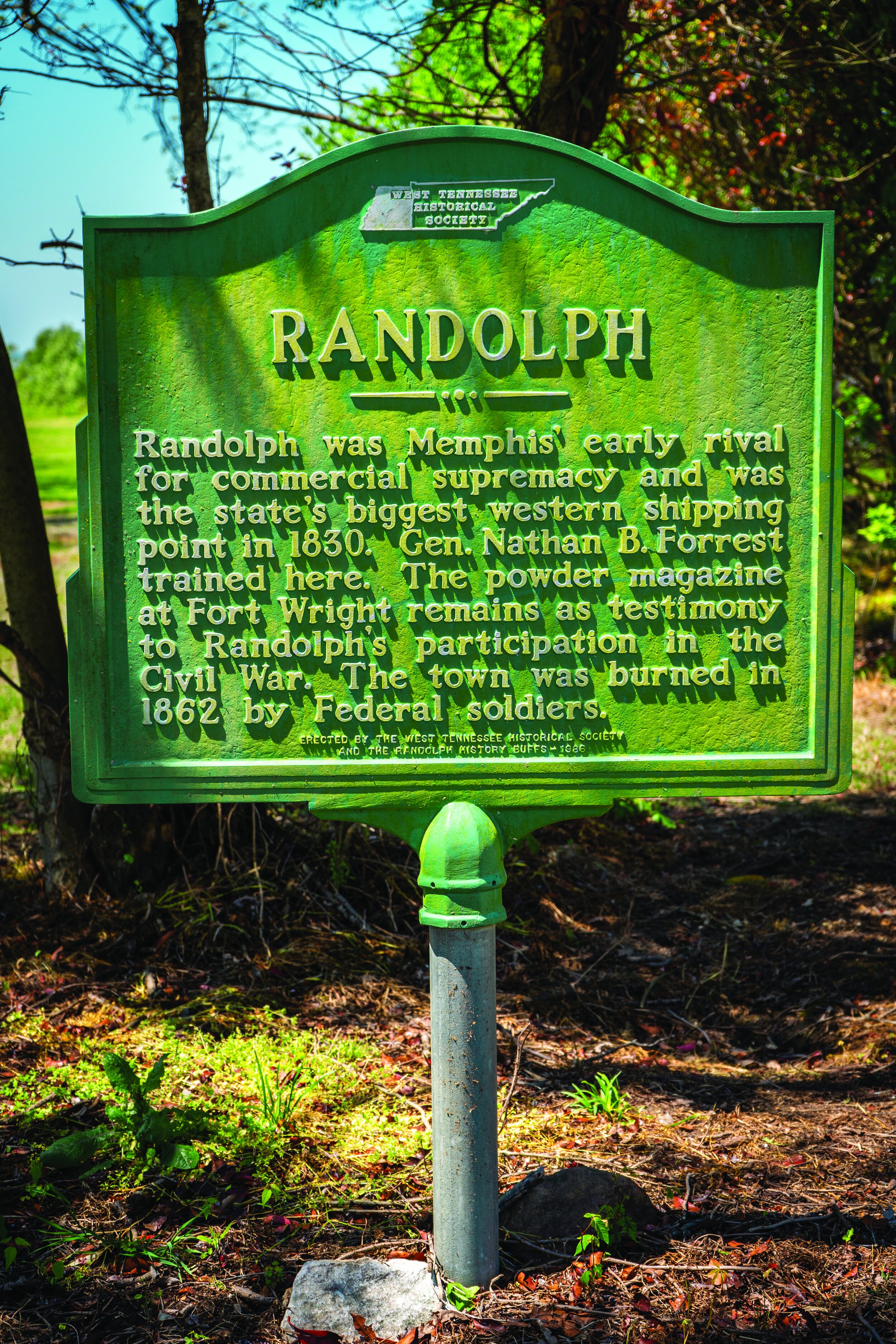

The Civil War started on April 12, 1861. Tennessee was the last state to officially secede from the Union on June 8, 1861—and was admitted to the confederacy on July 2, 1861. According to the 1982 Treasure of Recipes plus History of Randolph Cookbook that same year every county seat in Tennessee became a military camp. Around this same time, another source records that on January 20th of 1861, The Memphis Appeal published a pro-secessionist proposal to build a fort at Randolph to defend Memphis from invaders. As mentioned before, Randolph was situated on the 2nd Chickasaw Bluff. Building a fort at this portion of the Mississippi River would help keep the Union at bay if they followed at least a semblance of what the Confederacy thought they would do. Brigadier General Gideon J. Pillow sent a letter to LeRoy P. Walker, the Confederate Secretary of War, on April 26th, 1861 endorsing Randolph as “The most eligible situation for a battery to protect Memphis.” Within a few days, Governor Isham G. Harris ordered the establishment of a camp at Randolph. He sent 5,000 troops to complete the task. In four months the bluff was fortified. By June 1861, construction was not yet complete, but 50 cannons were reported ready at Fort Wright. During the summer of 1861, Nathan Bedford Forrest served as a private at Fort Wright in Randolph. The following months saw Fort Randolph constructed only months after Fort Wright in the fall of 1861.

In July of 1861, Fort Wright was reported as the forwardmost defensive position on the Mississippi River, but not the only defense. Fort Pillow was on the First Chickasaw Bluff, but even further North were the forts on Island Number 10 and at Columbus Belmont near Columbus, Kentucky, where they also put a large chain that stretched across the river from the Missouri banks to the Kentucky banks, held in place with huge anchors. Each of these forts were in place by the fall of 1861 to help protect the Mississippi River as well as the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers which are closer to and mostly in Middle Tennessee. Keeping these waterways free from the Union soldiers would have ensured a different outcome for the South.

The year 1862 saw a changing of the tides—gone were the months of preparations for the Northern invasion—the Union was present and fighting. In March 1862, Fort Randolph was described as a rough and “incomplete earthwork” in the New York Times. The fortification allows for a view of 6 miles. February had already seen the defeat of Forts DeRussey and Columbus just North of Tennessee. Union Troops from that battle went down the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers and defeated the weaker Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, which led to the siege of Nashville on February 24, 1862: the first Confederate capital to fall.

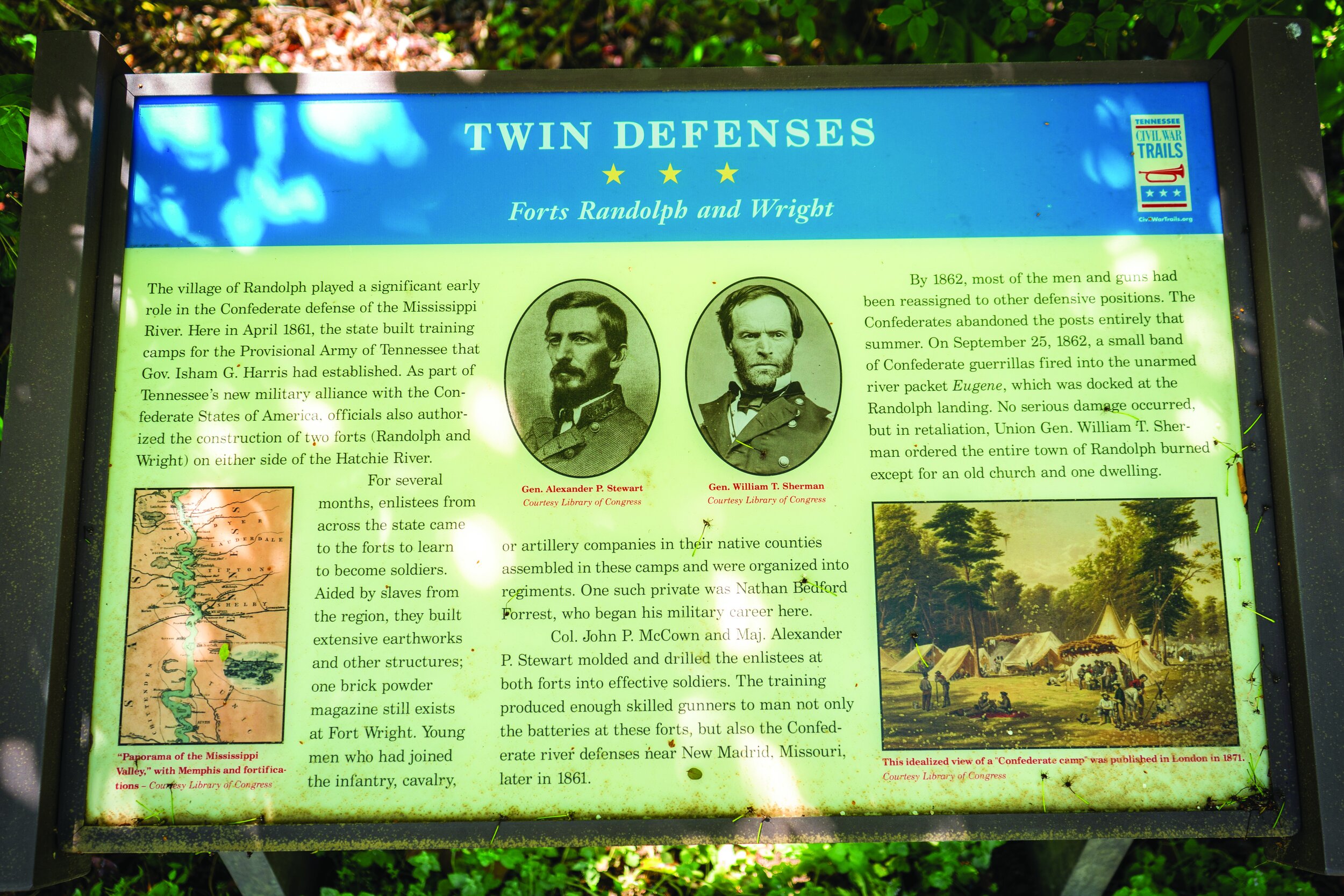

Markers at the site of Forts Randolph and Wright say this of the twin defenses, “The village of Randolph played a significant early role in the Confederate defense of the Mississippi River… Col. John P. McCown and Maj. Alexander P. Stewart molded and drilled enlistees at both forts into effective soldiers. The training produced enough skilled gunners to man not only the batteries at these forts, but also the Confederate river defenses near New Madrid, Missouri. By 1862, most of the men and guns had been reassigned to other defensive positions. The Confederates abandoned the posts entirely that summer.” On June 6th, 1862 the Battle of Memphis took place and Union troops occupied the city of Memphis until the end of the war. Then, “on September 25, 1862, a small band of Confederate guerrillas fired into the unarmed river packet Eugene, which was docked at the Randolph landing. No serious damage occurred, but in retaliation, Union Gen William T. Sherman ordered the entire town of Randolph burned except for an old church and one dwelling,” the home of J. M. Barton. Barton was a Mason, something he had in common with Sherman which is why he was spared.

Randolph’s burning was a precursor to Sherman’s March to the Sea. Having distinguished himself at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861, he was stationed around West Tennessee and served under Grant at the battles of Forts Henry and Donelson and the Battle of Shiloh. The March to the Sea lasted from November 15th, 1864 to December 21st, 1864, and reigned devastation across Georgia. This tactical warfare had its precursor in Randolph’s destruction. One source claims “97 businesses and houses were burned by the Yankees according to newspaper accounts,” but this information could not be backed up by Tipton County Historian David Gwinn. After the burning, he places "the population of the town between 1865 and 1900 at a little over 100.” Another description from the time says that there were only “half a dozen or so dilapidated frame houses.” Overall, whether it’s accurate to declare the devastation by Sherman’s troops a precursor to the March to the Sea, or not, is left to be determined. Sherman left lots of devastation in his wake everywhere he went during the Civil War destroying lots of towns, cities, and other communities, along with shooting every dog they saw. They did this because the dogs provided security and an alarm to the women and children left behind by the Confederate soldiers.

According to True Tales of Tipton, on October 27, 1864: “The steamer Belle Saint Louis is attacked by about 40 Confederates when it makes a nightfall landing at Randolph to take on a few bales of cotton. The Belle escapes capture when the alert captain has the boat backed quickly away from the bank.” This is the last act from Randolph during the Civil War. The 1982 Treasure of Recipes Cookbook recorded that at the beginning of the war, “the lawyers and doctors left their offices, merchants left their stores, the farmers and laborers left the fields, the young men left colleges—all that were fit for military service joined the Army.” This statement is fairly accurate for people in both the North and the South. So many men left to fight in the Civil War; the North lost an estimated 360,000 men and the South 258,000 making a total of 620,000 lives lost by the end of the war in 1865.

Randolph did try to rebuild after the war with little effect. In 1865, G. W. Perry opened the first store after the war. At some point in 1865, some sources quote that Randolph burned for the second time, discouraging many residents from rebuilding residences and business again. The next date reported about Randolph in True Tales of Tipton comes from 1883, when the second church was built at Randolph—a one-room Methodist Church.

On March 17th, 1883, a Memphis Newspaper mentions that steamboats are once again capable of landing at Randolph for the first time in ten years. Bad news strikes however because in 1885—Randolph burned down again. Only two general merchandise stores were not damaged. Finally, on March 19, 1913, Randolph reincorporated for the final time. There are no businesses, but a hope that there would eventually be a town sooner rather than later.

The 1982 Treasure of Recipes Cookbook lists 12 reasons for the decline of Randolph over its history. These reasons range from historically inaccurate things like “failure to secure the county seat in 1823” when Randolph wasn’t even incorporated to things that are accurate and did play a major part in why Randolph never became a metropolis like Memphis as it had been projected to be. Overall the Cookbook was an excellent source from the community to gage thoughts on Randolph.

David Gwinn was able to find a few references to Randolph in the 20th Century. Concerning school’s he found that “after the Civil War, there was a public school established on the bluff at Randolph. Over the years, various buildings were constructed, replaced, etc. In 1921 the school burned and was replaced. The school closed in 1949. The last class to graduate the eighth grade were Bernadine Morgan, Bonnie Pittman, Huey Paul Standridge, Thomas Hutcherson, Velma English, and Norma Jean “Tootie” Lott.” Concerning post offices in Randolph, Gwinn also recorded, “James M. Gibson was the first Postmaster followed by William P. Miller and Daniel Vaught. The date the Post Office was established is unclear in official records. The last Post Master was William H. Barton. Randolph Post Office closed in the 1930s and mail was redirected to Burlison.”

It would take years to accurately and completely gather a history of Randolph, Tennessee, but thanks to a few special people we were able to gather enough information for this three-part section of our Memories Series. Thank you to David Gwinn the Tipton County Historian for your research and the time you put into helping us with researching Randolph. Amy Turnage with the South Tipton County Chamber of Commerce provided the 1982 Treasure of Recipes plus History of Randolph Cookbook and a turn-of-the-century, historic newspaper. The South Tipton County Chamber of Commerce and Rosemary Bridges provided the books True Tales of Tipton and Tipton County, Tennessee: A Place of Memories—A People Moving Forward. Thank you to Bobby Jo and Willa Dru Stevens of Quito, Tennessee for providing books on the Civil War from the West Tennessee Historical Society and a newspaper clipping about the failed canal on the Hatchie River. Lee and Jo McMurray also provided valuable resources from the communities in and around Randolph. Finally, thank you to Dr. Murray Hudson and Sally Sawyers of Murray Hudson: Antique Maps, Globes, Books, & Prints for the digital versions of your maps. Thank you all for letting us use your resources to tell Randolph’s story!

All photos above are of the Powder Magazine at Forts Wright and Randolph. A hole was blown in the side during the war but was patched by preservationists. Another Powder Magazine is rumored to exist, but outside of those rumors, no one is quite sure where it is located.